Dr. Eva Nogales is also a professor of biochemistry, biophysics and structural biology at the University of California, Berkeley and a senior faculty scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

In this podcast, Berkeley Lab’s Eva Nogales describes how her team is using a new imaging technology that is yielding remarkably detailed 3-D models of complex biomolecules critical to DNA function. Using cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), Nogales and her colleagues have resolved the structure at near-atomic resolutions of a human transcription factor used in gene expression and DNA repair. Here she talks about her work and the technology’s promise in improving human health.

As reported in the journal Nature, the scientists usedcryo-EM to resolve the 3-D structure of a protein complex called transcription factor IIH (TFIIH) at 4.4 angstroms, or near-atomic resolution. This protein complex is used to unzip the DNA double helix so that genes can be accessed and read during transcription or repair.

“When TFIIH goes wrong, DNA repair can’t occur, and that malfunction is associated with severe cancer propensity, premature aging, and a variety of other defects,” said study principal investigator Eva Nogales, faculty scientist at Berkeley Lab’s Molecular Biophysics and Integrated Bioimaging Division. “Using this structure, we can now begin to place mutations in context to better understand why they give rise to misbehavior in cells.”

In this video, Berkeley Lab scientists simulate the cryo-EM structure of Transcription Factor II Human (TFIIH). The atomic coordinate model, colored according to the different TFIIH subunits, is shown inside the semi-transparent cryo-EM map. (Credit: Basil Greber/Berkeley Lab and UC Berkeley)

Human TFIIH is particularly fragile and prone to falling apart in the flash-freezing process, so researchers need to use an optimized buffer solution to help protect the protein structure.

These compounds that protect the proteins also work as antifreeze agents, but there’s a trade-off between protein stability and the ability to produce a transparent film of ice needed for cryo-EM,” said study lead author Basil Greber.

Biomolecules such as proteins are typically imaged using X-ray crystallography, but that method requires a large amount of stable sample for the crystallization process to work. The challenge with TFIIH is that it is hard to produce and purify in large quantities, and once obtained, it may not form crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction.

Enter cryo-EM, which can work even when sample amounts are very small. Electrons are sent through purified samples that have been flash-frozen at ultracold temperatures to prevent crystalline ice from forming.

Cryo-EM has been around for decades, but major advances over the past five years have led to a quantum leap in the quality of high-resolution images achievable with this technique.

Cryo-EM has been around for decades, but major advances over the past five years have led to a quantum leap in the quality of high-resolution images achievable with this technique.

When your goal is to get resolutions down to a few angstroms, the problem is that any motion gets magnified,” said study lead author Basil Greber, a UC Berkeley postdoctoral fellow at the California Institute for Quantitative Biosciences (QB3). “At high magnifications, the slight movement of the specimen as electrons move through leads to a blurred image.”

Making movies

The researchers credit the explosive growth in cryo-EM to advanced detector technology that Berkeley Lab engineer Peter Denes helped develop. Instead of a single picture taken for each sample, the direct detector camera shoots multiple frames in a process akin to recording a movie. The frames are then put together to create a high-resolution image. This approach resolves the blur from sample movement. The improved images contain higher quality data, and they allow researchers to study the sample in multiple states, as they exist in the cell.

Since shooting a movie generates far more data than a single frame, and thousands of movies are being collected during a microscopy session, the researchers needed the processing punch of supercomputers at the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC) at Berkeley Lab. The output from these computations was a 3-D map that required further interpretation.

When we began the data processing, we had 1.5 million images of individual molecules to sort through,” said Greber. “We needed to select particles that are representative of an intact complex. After 300,000 CPU hours at NERSC, we ended up with 120,000 images of individual particles that were used to compute the 3-D map of the protein.”

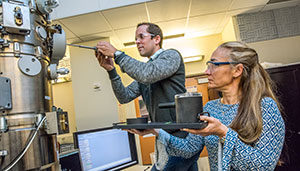

Berkeley Lab scientists Basil Greber (left) and Eva Nogales prepare to load samples into the “Titan” cryo-electron microscope at UC Berkeley’s Stanley Hall. (Credit: Marilyn Chung/Berkeley Lab)

To obtain an atomic model of the protein complex based on this 3-D map, the researchers used PHENIX (Python-based Hierarchical ENvironment for Integrated Xtallography), a software program whose development is led by Paul Adams, director of Berkeley Lab’s Molecular Biophysics and Integrated Bioimaging Division and a co-author of this study.

Not only does this structure improve basic understanding of DNA repair, the information could be used to help visualize how specific molecules are binding to target proteins in drug development.

In studying the physics and chemistry of these biological molecules, we’re often able to determine what they do, but how they do it is unclear,” said Nogales. “This work is a prime example of what structural biologists do. We establish the framework for understanding how the molecules function. And with that information, researchers can develop finely targeted therapies with more predictive power.”

Source: Berkeley Lab