In this special guest feature, Jon Bashor from LBNL writes that Exascale computing will accelerate the push toward clean fusion energy.

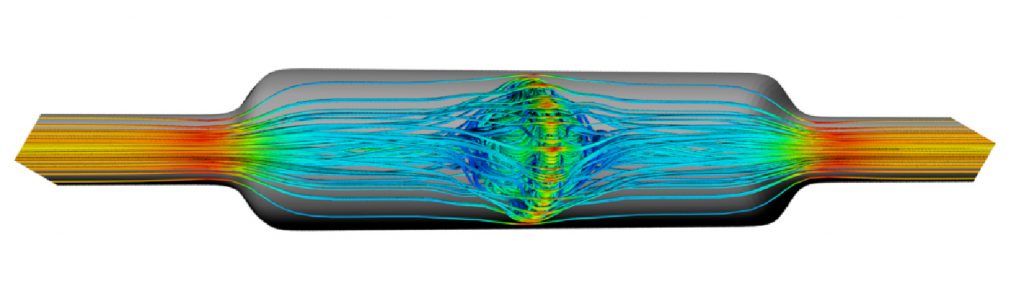

For decades, scientists have struggled to create a clean, unlimited energy source here on Earth by recreating the conditions that drive our sun. Called a fusion reactor, the mechanism would use powerful magnetic fields to confine and compress gases four times as hot as our sun. By using the magnetic fields to squeeze the gases, the atoms would fuse and release more energy than was used to power the reactor. But to date, that has only worked in theory.

Achieving fusion energy production would benefit society by providing a power source that is non-polluting, renewable and using fuels such as the hydrogen isotopes found in seawater and boron isotopes found in minerals.

Early fusion research projects in the 1950s and ‘60s relied on building expensive magnetic devices, testing them and then building new ones and repeating the cycle. In the mid-1970s, fusion scientists began using powerful computers to simulate how the hot gases, called plasmas, would be heated, squeezed and fused to produce energy. It’s an extremely complex and difficult problem, one that some fusion researchers have likened to holding gelatin together with rubber bands.

Using supercomputers to model and simulate plasma behavior, scientists have made great strides toward building a working reactor. The next generation of supercomputers on the horizon, known as exascale systems, will bring the promise of fusion energy closer.

The best-known fusion reactor design is called a tokamak, in which a donut-shaped chamber is used to contain the hot gases, inside. Because the reactors are so expensive, only small-scale ones have been built. ITER, an international effort to build the largest-ever tokamak-in the south of France. The project, conceived in 1985, is now scheduled to have its first plasma experiments in 2025 and begin fusion experiments in 2035. The estimated cost is 14 billion euros, with the European Union and six other nations footing the bill.

Historically, fusion research around the world has been funded by governments due to the high cost and long-range nature of the work.

But in the Orange County foothills of Southern California, a private company is also pursuing fusion energy, but taking a far different path than that of ITER and other tokamaks. Tri Alpha Energy’s cylindrical reactor design is completely different in its design philosophy, geometry, fuels and method of heating the plasma, all built with a different funding model. Chief Science Officer Toshiki Tajima says their approach makes them mavericks in the fusion community.

But the one thing both ITER and similar projects and Tri Alpha Energy have consistently relied on is using high-performance computers to simulate conditions inside the reactor as they seek to overcome the challenges inherent in designing, building and operating a machine that will replicate the processes of the sun here on Earth.

As each generation of supercomputers has come online, fusion scientists have been able to study plasma conditions in greater detail, helping them understand how the plasma will behave, how it may lose energy and disrupt the reactions, and what can be done to create and maintain fusion. With exascale supercomputers that are 50 times more powerful than today’s top systems looming on the horizon, Tri Alpha Energy sees great possibilities in accelerating the development of their reactor design. Tajima is one of 18 members of the industry advisory council for the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Exascale Computing Project (ECP).

As each generation of supercomputers has come online, fusion scientists have been able to study plasma conditions in greater detail, helping them understand how the plasma will behave, how it may lose energy and disrupt the reactions, and what can be done to create and maintain fusion. With exascale supercomputers that are 50 times more powerful than today’s top systems looming on the horizon, Tri Alpha Energy sees great possibilities in accelerating the development of their reactor design. Tajima is one of 18 members of the industry advisory council for the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Exascale Computing Project (ECP).

We’re very excited by the promise of exascale computing – we are currently fund-raising for our next-generation machine, but we can build a simulated reactor using a very powerful computer, and for this we would certainly need exascale,” Tajima said. “This would help us accurately predict if our idea would work, and if it works as predicted, our investors would be encouraged to support construction of the real thing.”

The Tri Alpha Energy fusion model builds on the experience and expertise of Tajima and his longtime mentor, the late Norman Rostoker, a professor of physics at the University of California, Irvine (UCI). Tajima first met Rostoker as a graduate student, leaving Japan to study at Irvine in 1973. In addition to his work with TAE, Tajima holds the Norman Rostoker Chair in Applied Physics at UCI. In 1998, Rostoker co-founded TAE, which Tajima joined in 2011.

In it for the long run

It was also in the mid-1970s, that the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, the forerunner of DOE, created a computing center to support magnetic fusion energy research, first with a cast-off computer from classified defense programs, but then with a series of ever-more capable supercomputers. From the outset, Tajima was an active user, and still remembers he was User No. 1100 at the Magnetic Fusion Energy Computer Center. The Control Data Corp. and Cray supercomputers were a big leap ahead of the IBM 360 he had been using.

The behavior of plasma could not easily be predicted with computation back then and it was very hard to make any progress,” Tajima said. “I was one of the very early birds to foul up the machines. When the Cray-1 arrived, it was marvelous and I fell in love with it.”

At the time, the tokamak was seen as the hot design and most people in the field gravitated in this direction, Tajima said, and he followed. But after learning about plasma-driven accelerators under Professor Rostoker, in 1976 he went to UCLA to work with Prof. John Dawson. “He and I shared a vision of new accelerators and we began using large-scale computation in 1975, an area in which I wanted to learn more from him,” Tajima said.

As a result, the two men wrote a paper entitled “Laser Electron Accelerator,” which appeared in Physical Review Letters in 1979. The seminal paper explained how firing an intense electromagnetic pulse (or beam of particles) into a plasma can create a wake in the plasma and that electrons, and perhaps ions, trapped in this wake can be accelerated to very high energies.

TAE’s philosophy, built on Rostoker’s ideas, is to combine both accelerator and fusion plasma research. In a tokamak, the deuterium-tritium fuel needs to be heated and confined at an energy level of 10,000 eV (electron volts) for fusion to occur. The TAE reactor, however, needs to be 30 times hotter. In a tokamak, the same magnetic fields that confine the plasma also heat it to 3 billion degrees C. In the TAE machine, the energy will be injected using a particle accelerator.

A 100,000 eV beam is nothing for an accelerator,” Tajima said, pointing to the 1G eV BELLA device at DOE’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. “Using a beam-driven plasma is relatively easy but it may be counterintuitive that you can get higher energy with more stability — the more energetic the wake is, the more stable it becomes.”

But this approach is not without risk. With the tokamak, the magnetic fields protect the plasma, much like the exoskeleton of a beetle protects the insect’s innards, Tajima said. But the accelerator beam creates a kind of spine, which creates the plasma by its weak magnetic fields, a condition known as Reverse Field Configuration. One of Rostoker’s concerns was that the plasma would be too vulnerable to other forces in the early stages of its formation. However, in the 40-centimeter diameter cylindrical reactor, the beam forms a ring like a bicycle tire, and like a bicycle, the stability increases the faster the wheels spin.

The stronger the beam is, the more stable the plasma becomes,” Tajima said. “This was the riskiest problem for us to solve, but in early 2000 we showed the plasma could survive and this reassured our investors. We call this approach of tackling the hardest problem first ‘fail fast’.”

Another advantage of TAE’s approach is that the main fuel, Boron-11, does not produce neutrons as a by-product; instead it produces three alpha particles, which is the basis of the company’s name. A tokamak, using hydrogen-isotope fuels, generates neutrons, which can penetrate and damage materials, including the superconducting magnets that confine the tokamak plasma. To prevent this, the tokamak reactor requires one-meter-thick shielding. Without the need to contain neutrons, the TAE reactor does not need heavy shielding. This also helps reduce construction costs.

Computation Critical to Future Progress

With his 40 years of experience using HPC to advance fusion energy, Tajima offers a long-term perspective, from the past decades to exascale systems in the early 2020s. As a principal investigator on the Numerical Tokamak project in the early 1990s, he has helped build much of the HPC ecosystem for fusion research.

At the early stage of modeling fusion behavior, the codes focus on the global plasma at very fast time scales. These codes, known as MHD codes (magnetohydrodynamics), are not as computationally “expensive,” meaning they do not require as many computing resources, and at TAE were run on in-house clusters.

The next step is to model the more minute part of the plasma instability, known as kinetic instability, which requires more sophisticated codes that can simulate the plasma in greater detail over longer time scales. Achieving this requires more sophisticated systems. Around 2008-09, TAE stabilized this stage of the problem using its own computing system and by working with university collaborators who have access to federally funded supercomputing centers, such as those supported by DOE. “Our computing became more demanding during this time,” Tajima said.

The third step, which TAE is now tackling, is to make a plasma that can “live” longer, which is known as the transport issue in the fusion community. “This is a very, very difficult problem and consumes large amounts of computing resources as it encompasses a different element of the plasma,” Tajima said, “and the plasma becomes much more complex.”

The problem involves three distinct functions:

- The core of the field reverse configuration, which is where the plasma is at the highest temperature

- The “scrape-off layer,” which is the protective outer layer of ash on the core and which Tajima likens to an onion’s skin

- The “ash cans,” or diverters, that are at each end of the reactor. They remove the ash, or impurities, from the scrape-off layer, which can make the plasma muddy and cause it to behave improperly.

“The problem is that the three elements behave very, very differently in both the plasma physics as well as in other properties,” Tajima said. “For example, the diverters are facing the metallic walls so you have to understand the interaction of the cold plate metals and the out-rushing impurities. And those dynamics are totally different than the core which is very high temperature and very high energy and spinning around like a bicycle tire, and the scrape-off layer.”

These factors are all coupled to each other using very complex geometries and in order to see if the TAE approach is feasible, researchers need to simulate the entirety of the reactor in order to understand and eventually control the reactions.

“We will run a three-layered simulation of our fusion reactor on the computer, with the huge particle code, the transport code and the neural net on the simulation – that’s our vision and we will certainly need an exascale machine to do this,” Tajima said. “This will allow us to predict if our concept works or not in advance of building machine so that our investors’ funds are not wasted.”

The overall code will have three components. At the basic level will be a representative simulation of particles in each part of the plasma. The second layer will be the more abstract transport code, which tracks heat moving in and out of the plasma. But even on exascale systems, the transport code will not be able to run fast enough to keep up with real-time changes in the plasma. Instabilities which affect the heat transport in the plasma come and go in milliseconds.

“So, we need a third layer that will be an artificial neural net, which will be able to react in microseconds, which is a bit similar to a driverless auto, and will ‘learn’ how to control the bicycle tire-shaped plasma, Tajima said. This application will be run on top of transport code and it will observe experimental data and react appropriately to keep the simulation running.

Doing this will certainly require exascale computing,” Tajima said. “Without it we will take up to 30 years to finish – and our investors cannot wait that long. This project has been independent of the government funding, so that our investors’ fund provided an independent, totally different path toward fusion. This could amount to a means of national security to provide an alternative solution to a problem as large as fusion energy. Society will also benefit from a clean source of energy and our exascale-driven reactor march will be a very good thing for the nation and the world.”

Plasma wakefield sidebar

Both particle accelerators and fusion energy are technologies important to the nation’s scientific leadership, with research funded over many decades by the Department of Energy and its predecessor agencies.

Not only are particle accelerators a vital part of the DOE-supported infrastructure of discovery science and university research, they also have private-sector applications and a broad range of benefits to industry, security, energy, the environment and medicine.

Since Toshiki Tajima and John Dawson published their paper “Laser Electron Accelerator” in 1979, the idea of building smaller accelerators, with the length measure in meters instead of kilometers, has gained traction. In these new accelerators, particles “surf” in the plasma wake of injected particles, reaching very high energy levels in very short distances.

According to Jean-Luc Vay, a researcher at DOE’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, taking full advantage of accelerators’ societal benefits, game-changing improvements in the size and cost of accelerators are needed. Plasma-based particle accelerators stand apart in their potential for these improvements, according to Vay, and turning this from a promising technology into a mainstream scientific tool depends critically on high-performance, high-fidelity modeling of complex processes that develop over a wide range of space and time scales.

To help achieve this goal, Vay is leading a project called “Exascale Modeling of Advanced Particle Accelerators” as part of DOE’s Exascale Computing Project. This project supports the practical economic design of smaller, less-expensive plasma-based accelerators.

To help achieve this goal, Vay is leading a project called “Exascale Modeling of Advanced Particle Accelerators” as part of DOE’s Exascale Computing Project. This project supports the practical economic design of smaller, less-expensive plasma-based accelerators.

As Tri Alpha Energy pursues its goal of using a particle accelerator (though this accelerator is not related to wakefield accelerators) to achieve fusion energy, the company is also planning to apply its experience and expertise in accelerator research for medical applications. Not only will this effort produce returns for the company’s investors, but it should also help advance TAE’s understanding of accelerators and using them to create a fusion reactor.

This article was made possible by the Exascale Computing Project.