Berkeley Lab researchers built a numerical model of the Cosumnes River watershed, extending from the Sierra Nevada mountains to the Central Valley, to study post-wildfire changes to the hydrologic cycle. (Credit: Berkeley Lab)

Researchers are using NERSC supercomputers to look at how California wildfires could affect water availability.

In recent years, wildfires in the western United States have occurred with increasing frequency and scale. Climate change scenarios in California predict prolonged periods of drought with potential for conditions even more amenable to wildfires. The Sierra Nevada Mountains provide up to 70% of the state’s water resources, yet there is little known on how wildfires will impact water resources in the future.

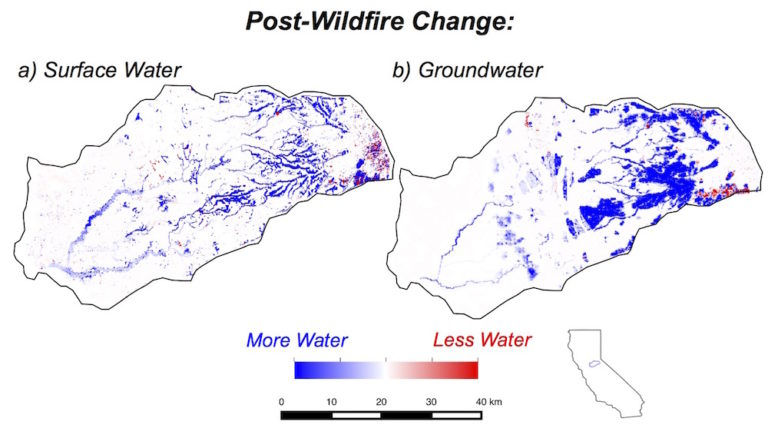

A new study by scientists at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) uses a numerical model of an important watershed in California to shed light on how wildfires can affect large-scale hydrological processes, such as stream flow, groundwater levels, and snowpack and snowmelt. The team found that post-wildfire conditions resulted in greater winter snowpack and subsequently greater summer runoff as well as increased groundwater storage.

The study, “Watershed Dynamics Following Wildfires: Nonlinear Feedbacks and Implications on Hydrologic Responses,” was published recently in the journal, Hydrological Processes.

We wanted to understand how changes at the land surface can propagate to other locations of the watershed,” said the study’s lead author, Fadji Maina, a postdoctoral fellow in Berkeley Lab’s Earth & Environmental Sciences Area. “Previous studies have looked at individual processes. Our model ties it together and looks at the system holistically.”

The researchers modeled the Cosumnes River watershed, which extends from the Sierra Nevadas, starting just southwest of Lake Tahoe, down to the Central Valley, ending just north of the Sacramento Delta. “It’s pretty representative of many watersheds in the state,” said Berkeley Lab researcher Erica Woodburn, co-author of the study. “We had previously constructed this model to understand how watersheds in the state might respond to climate change extremes. In this study, we used the model to numerically explore how post-wildfire land cover changes influenced water partitioning in the landscape over a range of spatial and temporal resolutions.”

The researchers modeled the Cosumnes River watershed, which extends from the Sierra Nevadas, starting just southwest of Lake Tahoe, down to the Central Valley, ending just north of the Sacramento Delta. “It’s pretty representative of many watersheds in the state,” said Berkeley Lab researcher Erica Woodburn, co-author of the study. “We had previously constructed this model to understand how watersheds in the state might respond to climate change extremes. In this study, we used the model to numerically explore how post-wildfire land cover changes influenced water partitioning in the landscape over a range of spatial and temporal resolutions.”

Using high-performance computing to simulate watershed dynamics over a period of one year, and assuming a 20% burn area based on historical occurrences, the study allowed them to identify the regions in the watershed that were most sensitive to wildfires conditions, as well as the hydrologic processes that are most affected.

Berkeley Lab researchers found that wildfires led to non-linear and bi-directional (positive and negative) changes in surface water and groundwater, even outside of the simulated burn scar areas of the Cosumnes River watershed. (Credit: Berkeley Lab)

Berkeley Lab researchers found that wildfires led to non-linear and bi-directional (positive and negative) changes in surface water and groundwater, even outside of the simulated burn scar areas of the Cosumnes River watershed. (Credit: Berkeley Lab)

Some of the findings were counterintuitive, the researchers said. For example, evapotranspiration, or the loss of water to the atmosphere from soil, leaves, and through plants, typically decreases after wildfire. However, some regions in the Berkeley Lab model experienced an increase due to changes in surface water runoff patterns in and near burn scars.

After a fire there are fewer trees, which leads to an expectation of less evapotranspiration,” Maina said. “But in some locations we actually saw an increase. It’s because the fire can change the subsurface distribution of groundwater. So there are nonlinear and propagating impacts of changing the land cover that leads to opposite trends than what you might expect from altering the land cover.”

Changing the land cover leads to a change in snowpack dynamics. “That will change how much and when the snow melts and feeds the rivers,” Woodburn said. “That in turn will impact groundwater. It’s a cascading effect. In the model we quantify how much it moves in space and time, which is something you can only do accurately with the type of high resolution model we’ve constructed.”

She added: “The changes to stream flow and groundwater levels following a wildfire are especially important metrics for water management stakeholders, who largely rely on this natural resource but have little way of understanding how they might be impacted given wildfires in the future. The study is really illustrative of the integrative nature of hydrologic processes across the Sierra Nevada-Central Valley interface in the state.”

Berkeley Lab researchers are also studying how the 2017 Sonoma County wildfires have affected the region’s water systems, including the biogeochemistry of the Russian River watershed. “Developing a predictive understanding of the influence of wildfire on both water availability and water quality is critically important for California water resiliency,” said Susan Hubbard, the Associate Laboratory Director of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Berkeley Lab. “High-performance computing allows our scientists to numerically explore how complex watersheds respond to a range of future scenarios, and the associated downgradient impacts that are important for water management.”

This research was funded by Berkeley Lab’s Laboratory Directed Research and Development (LDRD) program. The study used supercomputing resources at the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC) at Berkeley Lab to run the model. NERSC is a DOE Office of Science user facility.

Source: Berkeley Lab