By Dan Olds of Gabriel Consulting * Get more from this author

A couple of weeks ago I posted a blog here (Exascale by 2018: Crazy…or possible?) that looked at how long it took the industry to hit noteworthy HPC milestones. Chatter in the comments section (aside from the guy who assailed me for a typo, and for not explicitly calling out ‘per second’ denotations) discussed what these massive systems do and why they’re necessary.

A couple of weeks ago I posted a blog here (Exascale by 2018: Crazy…or possible?) that looked at how long it took the industry to hit noteworthy HPC milestones. Chatter in the comments section (aside from the guy who assailed me for a typo, and for not explicitly calling out ‘per second’ denotations) discussed what these massive systems do and why they’re necessary.

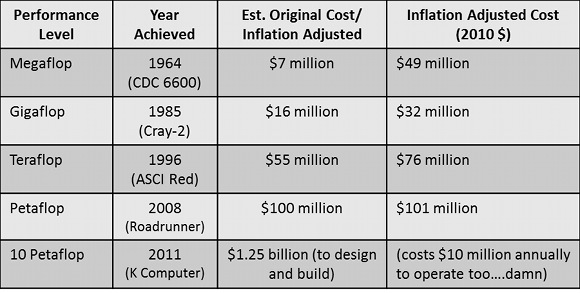

But Reg readers’ comments, plus others that I received via Twitter, raised some interesting questions that I’m going to attempt to answer – or at least sort of answer. The first is: just how much did these systems cost new?

When these systems came out, they were the biggest and baddest supercomputers in the world. But the price tag that the vendor attaches to a system in a press release and the actual price paid by the customer may have little or no relationship to each other or what the system cost to develop and build.

The price also varies depending on when in the product lifecycle you purchase the system. Buying the first one doesn’t mean that you’re necessarily paying the top price. If you’re the kind of customer who might buy boatloads of them, you would probably get a break. It also helps if you’re on the understanding side when it comes to performance qualification and bug fixes. Plus the right customer can validate a design, and that’s worth something to vendors.

In the table above, I did my best to find representative early-life prices for each system. It was easier to find prices for the later systems than for the CDC and Cray boxes. I found ranges of prices for the CDC and Cray-2 systems, so I took the average of those figures.

The final column adjusts those prices to 2010 dollars to level the playing field. Even though the cost of computing has gone down incredibly (as we’ll see below), the cost of BIG computing – the cost of the fastest system in the world – has increased considerably from the $50m CDC 6600 to the $101m IBM Roadrunner. The K computer is a bit of a special case. The $1.25bn figure supposedly represents the cost of design, development and the actual gear – but I don’t know if it’s an apples-to-apples comparison to the others.

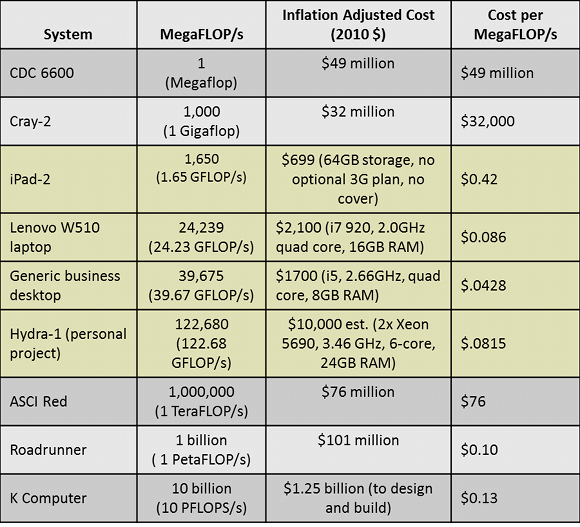

The second theme among readers’ comments was: how do these levels of performance (and associated prices) relate to the systems that we use day in and day out? This required some more Jethro Bodine ciphering time; I figured I’d benchmark some of the systems in our offices and see how they came out.

I wanted to use Linpack, so I first needed to find a distribution that works on our Windows 7 systems here. Yeah, yeah, I know that I should set up a dual boot with Linux and then run a ‘real’ Linpack in order to get better numbers, but I do have a regular day job.

Intel has a downloadable Linpack benchmark here that I put on three of our office systems. After perusing the documentation, I ran through some trial runs with different problem sizes in order to establish a performance range. What I found is that, on our systems at least, using the largest ‘typical’ problem set of 40,000 equations seemed to pull out the best Linpack average and peak results.

Our pal Jack Dongarra, one of the founders of the Top500 list, ran Linpack on an Apple iPad 2 and reported that the tablet hit between 1.5-1.65 GFLOP/s, which is higher than the Cray-2 back in 1985.

In the New York Times story, he also discussed the possibility of clustering iPads into a competitive supercomputer. He didn’t seem to feel that it would be a good price performer when compared to existing supercomputers, something that my research below confirms.

A bang-for-buck comparison

The table above is sorted in performance order. The yellowish rows represent the Apple iPad and some systems I have hanging off my office/home network. The astounding part of the table is the final column – the cost per MFLOP/s. What jumps out is that my wife’s generic business desktop computer kicks ass from a price/performance perspective. At less than 5 cents per MFLOP/s, it’s well ahead of everything else on the list.

The Lenovo W510 was billed as a “Mobile Workstation” when I bought it, and it’s the fastest laptop I’ve ever used. It’s also the heaviest and the most power-hungry, but with an Intel Extreme edition i7 mobile processor and a discreet NVIDIA Quadro graphics processor, it can handle the video processing I throw at it when I’m on the road.

A Bugatti of my own

The Hydra-1 system is something I’ve been working on for months, and it’s finally ready to come into service. I’m getting old enough to realize that I’ll never own a Bugatti Veyron ($2.4m) or even the much less expensive Ferrari Enzo ($670,000), but I can have the fastest computer in my state (until someone proves me wrong – plus it’s a small state).

I built Hydra-1 over the past several months, and it’s quite the screamer. A very helpful HPC vendor helped hook me up with two Intel Xeon 5690s which, together with 24GB of RAM, turned in a Linpack of 122.68 GFLOP/s at stock clock frequencies. Hydra-1 has some serious liquid cooling built in, so I have plenty of room for over-clocking, which might take the Linpack to 140 or better. I think I’m way under the Linpack theoretical max for the system, but I’m running the benchmark under Windows 7 without any tuning, so I’ll take what I can get.

The liquid cooling almost drove me out of my mind, but will definitely pay off on performance and comfort fronts. I’ve written some blogs about the whole process that I’ll submit to The Reg soon.

The iPad does okay, but not nearly as well as the typical systems in the chart. And the iPad numbers don’t include a 3G wireless plan or a cover – and the cheapest poly cover at the Apple store costs $39, or about 6 per cent of the total system price. And if you go with leather? At $69, that’ll drive your price per MFLOP up by 10 per cent.

The biggest surprise on our chart above? Look at Roadrunner and the K computer. Their cost per MFLOP/s is a mere 10 cents and 13 cents respectively. I ran the numbers again and again just to make sure I wasn’t dropping a zero (or adding one). But the result remains the same – the fastest and most modern supercomputers are much less per MFLOP than their predecessors.

So what have we learned today? First, even though the cost of computing components has dropped radically over time, the cost of building/buying the biggest landmark computers in the world has increased just as radically.

We’ve also seen that today’s home and business computers stack up very well against supercomputers of the past. The iPad 2 pwns the Cray 2 in Linpack, but costs 99.998 per cent less (leather case not included).

We’ve learned that the current chart-topping supercomputer, the K computer, has a competitive cost per MFLOP/s even though it cost something like $1.25bn to design and build.

But my wife’s desktop is the Linpack price/performance king, and now we know that too. ®

This article originally appeared in The Register. It appears here in its entirety as part of a cross-publishing agreement.