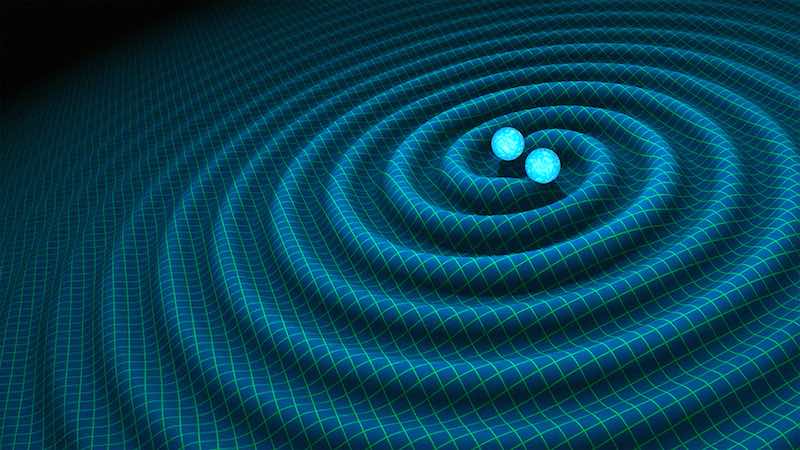

Researchers at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA), at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, working in collaboration with the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) have observed gravitational waves—ripples in the fabric of spacetime – for the second time.

Researchers at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA), at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, working in collaboration with the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) have observed gravitational waves—ripples in the fabric of spacetime – for the second time.

The NCSA’s role in this project is to create gravitational wave source models and accelerate the analysis of the data created by the LIGO observation runs.

Ed Seidel, director of the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, said: “NCSA is at the forefront of the most ambitious projects in multi-messenger astronomy that are already revolutionizing our understanding of the Universe. With NCSA now officially a member of the LIGO consortium, we expect to be having these types of announcements on a routine basis.”

“Gravitational wave astrophysics will enter a new phase during the second observing run,” said Eliu Huerta, head of the relativity group at NCSA and leader of the 18-member NCSA LIGO team at Illinois. “Given the detection rate during the first observing run last year, we expect to experience a swift transition from the first detections phase to the astrophysics phase, when we will be able to make strong inferences about the distribution of masses and angular momenta of black holes and neutron stars and possibly detect unexpected events. The work we are doing at NCSA on gravitational wave source modeling and data analysis will provide key insights.”

The gravitational waves were detected by both of the twin Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) detectors, located in Livingston, Louisiana, and Hanford, Washington. Physicists have concluded that the most recently observed gravitational waves were produced during the final moments of the merger of two black holes – 14 times and eight times the mass of the sun – to produce a single, more massive spinning black hole that is 21 times the mass of the sun.

Scientists stunned the world in February 2016 with the announcement of the first detection of gravitational waves, a milestone in physics and astronomy that confirmed a major prediction of Albert Einstein’s 1915 general theory of relativity, and marked the beginning of the new field of gravitational-wave astronomy.

On December 26, 2015, a second event was observed by researchers. Both discoveries were made possible by the enhanced capabilities of Advanced LIGO, a major upgrade that increases the sensitivity of the instruments compared to the first generation LIGO detectors, enabling a large increase in the volume of the universe that can be observed.

The nest run using advanced LIGO will begin this fall. By then, further improvements in detector sensitivity are expected to allow LIGO to reach as much as 1.5 to 2 times more of the volume of the universe. The Virgo detector is expected to join in the latter half of the upcoming observing run.

Eliu Huerta, head of the relativity group at NCSA and leader of the 18-member NCSA LIGO team at Illinois said: “Gravitational wave astrophysics will enter a new phase during the second observing run. Given the detection rate during the first observing run last year, we expect to experience a swift transition from the first detections phase to the astrophysics phase, when we will be able to make strong inferences about the distribution of masses and angular momenta of black holes and neutron stars, and possibly detect unexpected events.”

The work we are doing at NCSA on gravitational wave source modelling and data analysis will provide key insights’ concluded Huerta.

The LIGO Observatories are funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and were conceived, built, and are operated by the US universities Caltech and MIT. This recent discovery accepted for publication in the journal Physical Review Letters, was made by the LIGO Scientific Collaboration (which includes the GEO Collaboration and the Australian Consortium for Interferometric Gravitational Astronomy) and the Virgo Collaboration using data from the two LIGO detectors.

This story appears here as part of a cross-publishing agreement with Scientific Computing World.